From the ancient ikat to the royal patola, from jamdani to Banarasi brocade to the ornate gyaser, and the Kashmiri pashmina, here are some of India’s most famous handwoven and handspun weaves that celebrate rare artisanal flair to create the most unique and opulent fabrics

By Priya Kumari Rana

26 January 2023

Handloom fabric is the pulse of India, and has been a tradition in ourland since millennia. India is one of the few countries where handloom and hand-spinning are still thriving. In his recent ‘Mann ki Baat’ address to the nation, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi spoke about National Handloom Day (celebrated on August 7) and encouraged citizens to support handloom artisans, which, in turn,would add to the vision of “Vocal for Local”.

From khadi, which has its roots in our movement for Independence, when Mahatma Gandhi encouraged Indians to start spinning yarn with a charkha (spinning wheel) at home, to clusters of weavers spread all over India who spin and weave indigenous cloth – whether it’s ikat, bandhni, patola, Banarasi brocades, zari, Apatani, or pashmina – cloth made on the hand-operated loom is woven within the fabric of our nation.

Khadi

Khadi, the most humble yet potent symbol of India’s freedom struggle, needs to be certified by the Khadi Village Industries Commission (KVIC), for it to be able to carry the name – and the cloth must be handspun and handwoven. The fabric is mostly woven in KVIC-recognised

and supported institutions where the government provides employment to rural weavers.

Ikat

Ikat is a truly mysterious weave, with an Egyptian mummy discovered with a piece of Odisha ikat – a proof of the trade routes between the two ancient civilisations. References to ikat have been found in the murals of the Ajanta caves from 200 BC. Ikat, unlike other forms of tie-and-dye, is unique because here it’s the yarn that is first dyed (by mashing together bundles of yarn tied tightly together, dyed in the pattern of your choice), and then the weaver takes the yarn, and lines it up on the loom to create a pattern on it – a very laborious and intricate process.

There is warp ikat, weft ikat, and double ikat, which is very intricate, and it’s manufactured in Odisha, Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh. Veteran designers like Madhu Jain, have made ikat their métier by creating museum-worthy pieces in bamboo silk in the ikat styles of Indonesia, Uzbekistan, and India. Jain has been vocal in her support of sustainable fabrics and living, and this new textile does not eat into the earth’s resources, and can provide livelihood to bamboo growers, besides being biodegradable.

motifs that have been hand embroidered on the fabric.

still retain its original colour! A Paan Patola is a double ikat weave from the northern Gujarat region of Patan and is a priceless heirloom that are passed down from one generation to the next. Each piece of coloured (dyed) yarn is carefully aligned so as to form the desired pattern while weaving, and both the warp and weft are dyed whilst making this kind of Patola. Natural dye like madder roots, indigo, and turmeric are used to colour the thread, and patterns look identical on both sides. Delhi-based fashion label Asha Gautam recently created a phenomenal Patola sari for actor Urvashi Rautela, which took six months to make – with more than 70 days to colour the threads, and 25 days to weave, and with 600 gm of silk.

Banarasi Brocade

The Pilikothi area of Varanasi is the centre of the world-famous Banarasi brocade, which involves intricate motifs in zari handwoven onto silk cloth, producing some of the finest sarees, typically worn by a bride on her wedding day. Kolkata-based designers and textile revivalists Swati and Sunaina are known for their delicately woven tissue saris with one side silk, and the other side pure zari, with borders in Hashiya miniature paintings in brocade. Each saree takes around eight months to weave and costs around INR 2 lakh. The ornate Gyaser weave (traditionally made for the heavy robes of Buddhist monks in monasteries in Tibet and Lhasa) was brought to Varanasi from China by traders. This Oriental influence can also been seen in today’s Banarasi sarees.

Shanti Banares, based in Varanasi, is a third-generation textile brand specialising in Banarasi weaves, and is led by Amrit and Priyanka Shah. In one of their recent collections, they have used Persian weaves to create bird motifs – unusual in Banarasi saris, using antique-finish zari. “To make a loom, the weaver normally makes a jacquard (a pattern that is woven in a certain ratio of under and over threads) that comes on the loom,” says Amrit Shah. “But when there is no jacquard, the weaver takes a motif and weaves on it like a drawing – a technique known as uchyant, where each motif is woven separately.”

Apatani Weave

This weave is prevalent in every home of the Apatani community in Arunachal Pradesh (and parts of Nagaland) even today, although unfortunately, the number of families practising it has been declining.

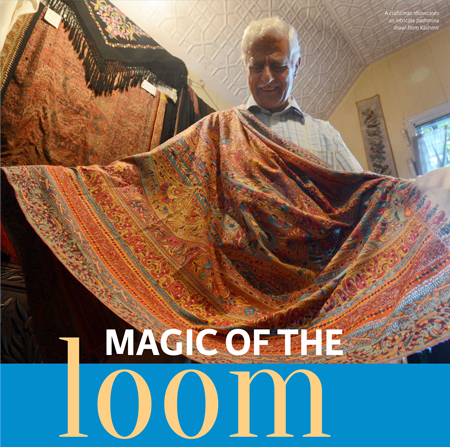

Pashmina

Next we travel to the picturesque, wintry setting of Kashmir, which produces the warm and comforting pashmina weave. A 100 per cent pashmina must be made from 100 per cent cashmere to be considered premium, and only gets the GI (Geographical Indication)

certification if it’s handspun and handwoven using pure pashmina wool from Ladakh. “The wool for the pashmina we make is from goats from the Chand Khand region of Ladakh,” says Tariq Ahmad Dar, a former model who runs his own luxury pashmina brand, Pashmkaar.

“The pashmina was the first economic revolution in Kashmir, especially for women,” says Dar, adding, “My grandmother would spin yarn on a charkha, and even today the yarn cannot be made without women.”

The above are just a few of the handloom textile traditions practised in India. But there are many more that are flourishing in different parts of the country. With support from the government, designers and textile revivalists are working towards popularising these fabrics

again. Promotion of the ‘India Handloom Brand’, cultural diplomatic engagements and the support of indigenous artworks are some of the important steps being taken toward promoting this industry.

Also effective are implementation of government schemes such as the “Make in India” and “Vocal for Local” to promote handlooms and crafts; the Mudra scheme to support women entrepreneurs, the National Rural Livelihoods Mission, and mobilising SHGs are other bottomup approaches. But what is most important, is the support people can offer in the revival of these weaves by buying and wearing them.

*Priya Rana is a leading fashion writer who has helmed major publications in India. Rana is currently a contributing editor with The Man magazine.

(It may kindly be noted that the views expressed in this article are personal.)