Reaffirming Women as the Custodians of our Heritage, Humanity and Future

By Jaimal Anand

14 September 2020

This article will attempt to draw a link between Women’s Month and Heritage Month. The role of women in defining and protecting our heritage is not often linked but is, in my view, critical. The narratives that have been selected for this piece build on a position that women are a powerful force, and that this force has been supressed by centuries of patriarchal conditioning.

This article will attempt to draw a link between Women’s Month and Heritage Month. The role of women in defining and protecting our heritage is not often linked but is, in my view, critical. The narratives that have been selected for this piece build on a position that women are a powerful force, and that this force has been supressed by centuries of patriarchal conditioning.

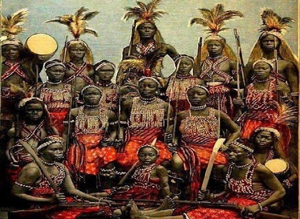

Photo: A fierce all female military squad in the kingdom of Dahomey (hadithi.africa)

All women have an innate strength and a special sort of courage that most men are unable to understand, however, during times of crises we have all seen this explosive force in action. The lens through which we, as men, perceive woman must change. One way of ensuring this is to drive to the fore narratives of women who literally shook the world, yet somehow their stories are overshadowed or stifled for reasons we may well understand, but not admit to. It is therefore important that mind-sets are changed at a societal level.

Dulcie September Square in Paris, France, was officially inaugurated on 31 March 1998. The name plate reads: "Dulcie September Square: Representative of the African National Congress: Assassinated in Paris on 29 March 1988".

September is among the many life stories shared by millions of women in South Africa, Africa and the world. Her story stands out as a tale of courage and fortitude that is the embodiment of our heritage and our millennia-old emblems of true humanity. The events of 29 March 1988, when the 53-year-old September was assassinated while opening the African National Congress (ANC) office in Paris are well documented: she was shot five times with a 22-calibre rifle.

Georges Marchais of the French Communist Party strongly criticised the French Government, and on 31 March 1988, Alain Guerin in L’Humanite, reported on special death squads that were operating in Europe. At her funeral, 20,000 mourners offered their last respects. September was a woman and high-ranked ANC diplomat who fell on foreign soil for the liberation of our people. September personified the emblems and virtues of the liberation movements through history. She was an internationalist, an activist, a warrior, a leader and above all an ordinary South African with an extraordinary dose of courage and principles. Despite her caring and gentle demeanour, she was clearly seen as a very real and dangerous threat.

September’s determination and sense of morality were reflected in her deep involvement with the Albertini Affair, that impacted negatively on the diplomatic relations between France and (an increasingly isolated) South Africa between 1986 and 1987. French national Pierre Andre Albertini was part of the French Government’s exchange programme and arrived in South Africa as a French language lecturer at the University of Fort Hare. Albertini became politically active, and was imprisoned for his collaboration with the ANC. September had become active in mobilising the Anti-Apartheid Movement, and petitioned French President François Mitterrand not to accept the credentials of South Africa’s new Ambassador to France until Albertini had been released from his Ciskei prison and allowed to return home.

September had fused an effective anti-apartheid lobby by driving the sanctions and disinvestment campaigns. Her activities were not limited to Paris –she also mobilised widely in Switzerland and Luxembourg. Her activism became a serious threat to the South African regime and supporters of the regime in the international community.

Like many others, her life was symbolic of deep compassion and a humane bearing that cost her, her life.

Women of war

The 21st century has become a terrain in which the order of the 20th century is being challenged and eroded. The 20th century was fascinating in many respects; it was a stage in which progressive values were being advanced mainly by post-colonial states, side by side with conservativism that remained firmly entrenched in the world order.

Svetlana Alexievich’s 2017 publication, “The Unwomanly Face of War”, is a harsh and very real story of female soldiers of the Soviet Union who served with distinction during World War II. In her review of the book, Liza Mundy1 describes a scene where a group of female fighters arrive at the front in their combat attire. These women were new graduates of the Soviet Union’s women’s sniper school, and were assigned to the 62nd Rifleman’s Division. She cites a very specific story where the commander was annoyed to see female soldiers arrive at the front, and asked if “they’ve foisted girls on me”. In his irritation, the commander then orders them to prove they can shoot, camouflage themselves and perform other key mandatory combat-oriented tasks.

While watching them train, he stepped on a hummock and was taken aback when the ground below him said “you’re too heavy”. The voice was that of a female sniper embedded in the landscape. The commanding officer then said”: “I take back my words” and conceded amid their laughter. Tragically, the story goes on to detail the abuse that these women endured after their service, mainly from their family members and communities. This forced many to not to disclose their military service, and the world nearly lost this legacy and history.

The Sparta of Africa

Similarly in Africa, there is a little known history of the Dahomean warrior women. The Kingdom of Dahomey was a highly militaristic West African kingdom that was located in what is present-day Benin. It existed from about 1600 until 1904, and the Kingdom had a diplomatic presence in Brazil since 1750 and interacted diplomatically with Portugal and France as regional actors of the time.

With time, the Dahomean State became famous for its corps of ferocious female soldiers. Their origins are unclear, but most likely emerged out of female hunting teams. They were organised around 1729. The women reportedly behaved so courageously they became a permanent corps. Eventually, they became decorated to the point that King Ghezo ordered every family to send him their daughters, with the fittest being chosen as soldiers.

In 1861, a missionary by the name of Francesco Borghero was summoned to a parade ground in Abomey, the capital of the Kingdom of Dahomey. At that time, Dahomey was known in Europe as a “Black Sparta,” a fiercely militaristic society bent on conquest. As a sign of friendship, King Glele presented his army to his European guest. Father Borghero noted 3 000 heavily armed soldiers marching into the square. He described the Dahomean troops as a fearsome sight, barefoot and bristling with clubs and knives, and a good part of this army were female.

The First Franco-Dahomean War in 1890 resulted in two major battles, one of which was really bloody and significant. It took place in heavy rain, at dawn and just outside Cotonou. The Dahomey army, which included formidable female units, assaulted a French formation, which was forced to fall back after a ferocious battle with hand-to-hand combat. The French won the day due to their heavy firepower, but in the battle’s aftermath a French officer found a woman warrior called Nanisca lying dead and described the scene. “The cleaver, with its curved blade, engraved with fetish symbols, was attached to her left wrist by a small cord,” he wrote, “and her right hand was clenched around the barrel of her carbine covered with cowries2.”

Pirates and warlords

Pirates are often associated with bearded buccaneers or peg-legged menaces known as Blackbeard, Barbarossa or Calico Jack. However, there were women among these raiders who were equally ruthless and feared and sailed the seven seas for centuries.

Laura Sook Duncombe’s 2017 publication, “Pirate Women: The Princesses, Prostitutes, and Privateers Who Ruled the Seven Seas” demonstrates that history has largely ignored the legacy of female pirates. Legendary pirates like Sayyida al-Hurra in 1510 AD of the Barbary (North African) corsairs controlled the Western Mediterranean and was in alliance with Barbarossa of Algiers. These formidable women sailed with and in command of male pirates who were incredibly dangerous and violent. For her exploits, Sayyida al Hurra held the title Hurra that translates to “Queen” or “noble lady who is free and independent” or” the woman sovereign who bows to no superior authority”.

These women came from all walks of life, but had one thing in common, a desire for freedom. Their exploits and adventurism can be traced as far back as Queen Teuta of Illyria, who ruled after her husband’s death in 231 BC. Her reputation was amplified when the Romans sent representatives to Teuta for a diplomatic meeting to halt the raids on their cargo. She brushed them off, claiming that her tribe saw what they called piracy, as a lawful trade. Diplomacy ended at that point, one Roman Ambassador was killed, while the other was imprisoned, bringing her in conflict with Rome.

A Chinese pirate, Ms Cheng, is listed as one of history’s most successful pirates. Her husband died in 1807, and she partnered with his trusted lieutenant named Chang Pao. She raided Southeast Asia and across the Indian Ocean, assembled a sizable fleet and penned a rigorous code of conduct for her pirates.

Importantly, she decreed that the rape of female prisoners was punishable by beheading, and deserters had their ears lopped off. Ms. Cheng’s reign made her public enemy number one to the Chinese Government at the time. In 1810, the British and Portuguese navies were enlisted to bring her to justice. With a stroke of strategic brilliance, she agreed to surrender her fleet and lay down her sword in exchange for the right to keep her (ill-gotten) riches. She negotiated safe passage and a secure pension for her sailors as part of the surrender agreement. Ms Cheng retired as one of history’s most successful pirates, and went on to run a gambling house until her death in 1844 at the age of 69.

Conclusion

On 24 August 2020, Reneva Fourie3 penned an article, titled: “Time to Ditch the Phrase ‘building the capacity of women’” In the title, she correctly challenges the language and the psychology that reinforce patriarchy. Reflecting on the life of Dulcie September, many other South African women, freedom fighters and those leading relatively regular lives with highly irregular daily battles, it is unacceptable to continuously speak of capacitating women. Its patronising, it presumes incapacity and perpetuates the mind-set of oppression and is deaf to the fact that women are indeed capacitated.

This article has barely covered the volumes that have been documented about heroic women. The female force is without dispute the most formidable force on earth. When we hear of incidents of gender-based violence, rape and abuse, which have reached disturbing proportions, as men we must hang our heads in shame.

Men who take to such despicable behaviour are afraid of the legacy and heritage that women have given humanity. This article tries to present women who were equals to powerful and dangerous men like Barbarossa of Algiers who were able to respect women as their allies (equals). It can only be mentally weak and fearful men that behave in such a despicable fashion.

The only reason why Dulcie September had to die violently is because she was a threat to the Apartheid regime, and same with the descendants of the women of Benin, the women who sailed the seven seas and those who fought toe to toe on any battlefield.

I will end by saluting the regular, day-to day-women that we must not forget to honour. This is the mother who works 12-hour shifts to feed her family, the teenage orphan or the grandmother who has the responsibility of raising children with little or no resources, the woman who tills the soil in the rural settings, the woman who puts her own scars aside and helps a society heal after the horrors of violence, abuse and even war. The list goes on, and often in our enthusiasm to narrate the stories of those who lead, we forget to celebrate the true, community-based builders of our nation.

1Liza Mundy is author of Code Girls Untold Story of the American Codebreakers of World War II

2 https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/dahomeys-women-warriors-88286072/